Published 2021-06-18

Keywords

- Steno,

- Crystal growth,

- Quartz,

- Interfacial angles,

- Stenonite

How to Cite

Copyright (c) 2021 Silvio Menchetti

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Abstract

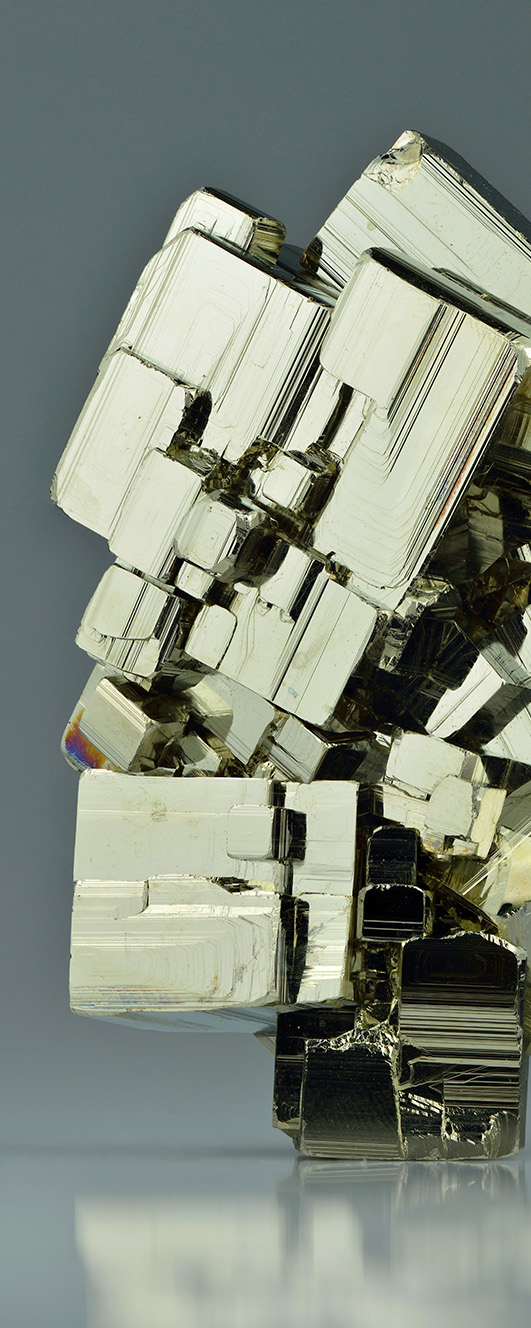

Steno (1638-1686) operated in a historical context rich of discoveries and observations done by previous scientists such as Vannoccio Biringucci, Georg Bauer (Agricola), Johannes von Kepler, Robert Hooke, Christiaan Huyghens, Erasmus Bartholin, and others. Steno also had to fight against some irreducible dogmatic and “mythological” beliefs, such as the vis formativa and succus lapidescens, supported by e.g. Michele Mercati and Anselmo Boetius de Boot, respectively. In De solido intra solidum naturaliter contento dissertationis prodromus Steno deals with almost all aspects of Earth Sciences and not just "solid inclusions" as it might seem from the full title of the Prodromus. This contribution deals only with aspects related to crystallography and minerals in general. The most famous is highlighted by the sentence “non mutatis angulis” which is a clear reference to the fact that interfacial angles of quartz crystals do not change regardless of the size and the number of the faces. This observation was then generalized as a law for all minerals by Jean-Baptiste Romé de l’Isle a century later. Less well known but of great importance is Steno’s assertion that the crystals grow thanks to the addition of particles that come from an external fluid and are not “fed” from the inside like in vegetables; moreover, the speed of growth is not the same for all faces. For example, the faces of the “pyramid” in quartz can grow more or less rapidly than those of the prism (giving rise to either squat or elongated crystals). It can therefore be argued that Steno has greatly contributed to the concept of anisotropy in the solid state, typical of all crystals. Stenonite, Sr2Al(CO3)F5, is a new mineral dedicated to his memory about sixty years ago.