Published 2022-12-07

Keywords

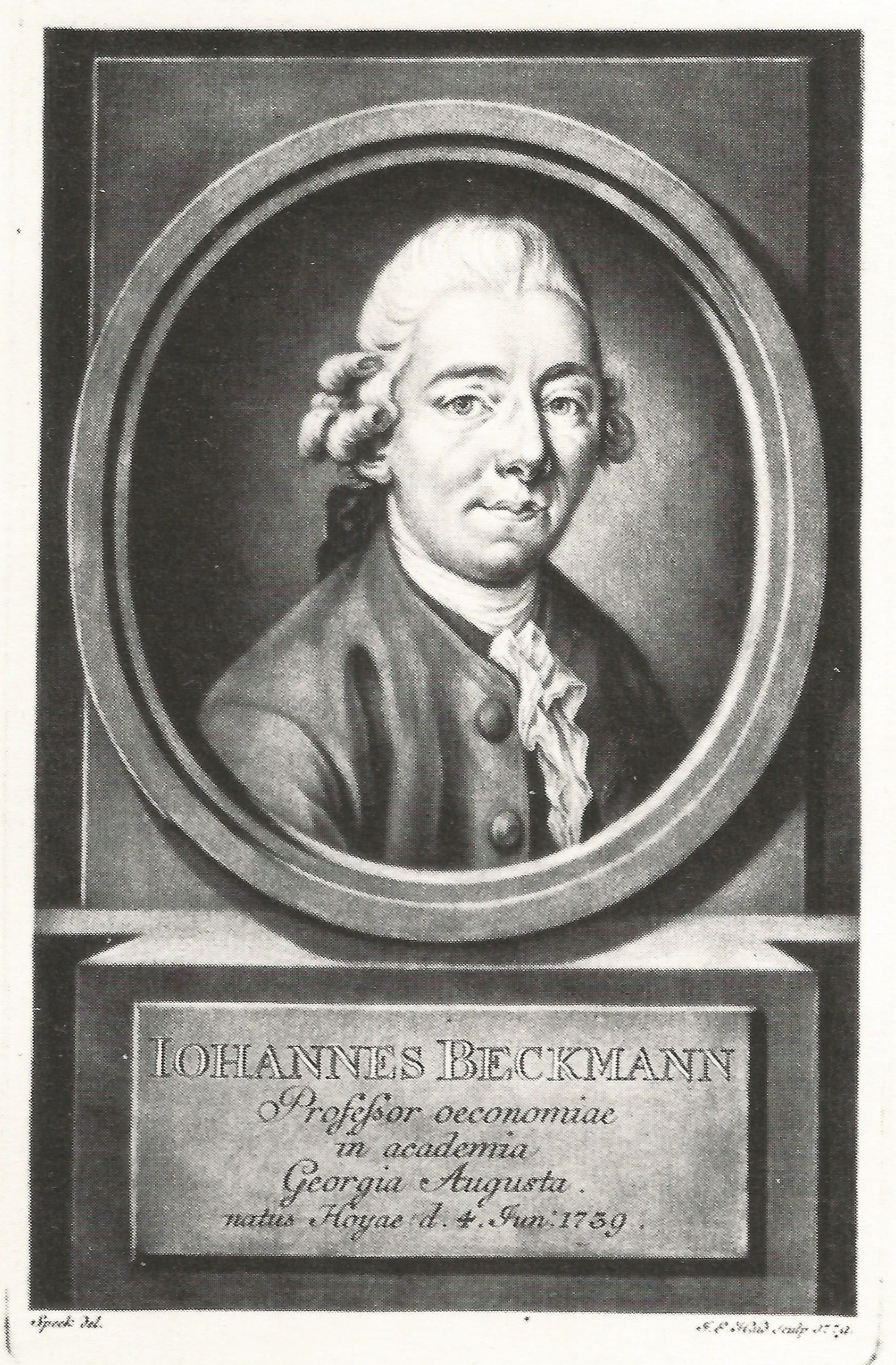

- Johann Beckmann,

- history of chemical technology,

- practical chemistry before Beckmann,

- cameralism and chemia applicata,

- sugar industry

- refutation of criticism of technology ...More

How to Cite

Copyright (c) 2023 Juergen Heinrich Maar

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Abstract

Modern chemical technology, in the humanistic spirit of the Enlightenment, begins with Johann Beckmann (1739-1811). It followed pre-modern technologies associated with Cameralism and Chemia Applicata. Beckmann’s holistic approach to technology, expressed in “Anleitung zur Technologie” (1777) and “Entwurf einer Allgemeinen Technologie” (1806), also engages with economic, social, cultural and ethical problems, giving the term ‘technology’ a new meaning. Viewed with skepticism in his time, there was a revival of Beckmann’s ideas by Franz Exner (1840-1913) in 1878. Only in recent decades his contribution to technology was more extensively studied. Examples of Beckmann’s ideas are presented.

References

- G. Sarton, “The History of Science and the New Humanism”, Cambridge/Mass. Harvard University Press, 1966, p. liv.

- Unamuno, M., “Del Sentimiento Trágico de la Vida”, Editorial Alianza, Madrid, 2008, p. 307. (Original Spanish edition 1912; English translation, ‘Tragical Sense of Life, by J. Crawford Flitch, 1913).

- Jacomy, B.,”A Era do Controle Remoto”, Editora Zahar, Rio de Janeiro, 2002, p. 103.

- Weyer, J., Chemie an einem Fürstenhof der Renaissance, Chemie in unserer Zeit, 12, 241-249 (1992).

- Thurneysser was a controversial figure, and his work in this field is lesser known. Older historiography (e.g.Stillman) considers him an adventurer, but more recent research shad a new light on his multiple interests (e.g. B. Herold, História Natural de Portugal, Ágora, nº 19, 305-334 (2017).

- Newman, W., Principe, L., Alchemy vs Chemistry: the Etymological Origins of a Historiographic Mistake, Early Science and Medicine, 3, 32-65 (1998), p. 32.

- Debus, A., “The Chemical Philosophy”, Dover, New York, 2002 [1977].

- Schmauderer, P., Glaubers Einfluss auf die Frühformen der Chemischen Technik, Chemie Ingenieur-Technik, 42, 686-696 (1970),

- Soukup, R., “Chemie in Österreich”, Vienna, Böhlau. 2007, pp. 443-455.

- Stillman, J. “History of Alchemy and Early Chemistry”, New York, Dover, 1960 [1924], p. 420.

- Lärmer, K., Johann Kunckel der Alchemist auf der Pfaueninsel, Berlinische Monatschrift, 2000, pp.10-16.

- Rau, H., Johann Kunckel, Geheimer Kammerdiener des Grossen Kurfürsten, und sein Glaslaboratorium auf der Pfaueninsel in Berlin, Medizinhistorisches Journal, 11, 129-148 (1976).

- Soukup, R., “Chemie in Österreich”, Böhlau, Vienna, 2007, p. 414.

- Roche, M., “Early History of Science in Latin America,” Science, 164, 806-810 (1976).

- Wisniak, J., Jean Hellot. A pioneer of chemical technology, Revista CENIC Ciencias Químicas, 40, 111-121 (2009).

- Meinel, C., Reine und Angewandte Chemie. Die Entstehung einer neuen Wissenschaftskonzeption in der Chemie der Aufklärung, Berichte zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte, 8, 25-45 (1985).

- Frison, G., The First and Modern Notion of Technology from Linnaeus to Beckmann and Marx, Consecutio Rerum, Anno III, nº 6, 147-162, (2018), p. 152.

- Meinel, C., Artibus Academica Inserenda. Chemistry’s place in eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries Universities, History of Universities, 8, 89-115 (1988).

- Meinel, C., Theory or Practice? The Eighteenth-Century Debate on the Scientific Status of Chemistry, Ambix, 30, 121-132 (1983).

- Linde, R., Johann Conrad Barkhausen (1666-1723) – der bedeutendste Sohn der Stadt Horn in Lippe, Lippische Mitteilungen aus Geschichte und Landeskunde, vol. 53 (1964).

- Frison, G., The First and Modern Notion of Technology from Linnaeus to Beckmann and Marx, Consecutio Rerum, Anno III, nº 6, 147-162, (2018), p. 148.

- Beckmann, J., “Anleitung zur Technologie”, Vandenhoeck, Göttingen, 1777

- Lühmann-Frester, H., “Europa in der frühen Neuzeit”, Böhlau Verlag, Vienna, 1999, Vol. 5, (Ed. E. Donnert), pp. 627/628.

- Exner, W., Johann Beckmann, Begründer der Technischen Wissenschaft, Hoya, Johann Beckmann Gesellschaft, 1989, introduction. This is a facsimile reprint of Exner’s original edition, Vienna, Carl Geralds, 1878.

- Biographies of Beckmann may be found e.g. in Exner’s book from 1878 (reprint 1989), or in O. Gekeler, Johann Beckmann and the Consideration of Commodities and Technology in their Entirety, Sartoniana, 2, 139-171 (1989).

- Klemm, F. “Geschichte der Technik”, Rowohlt, Hamburg, 1983. See also W. König, H. Schneider, “Die Technikhistorische Forschung in Deutschland seit 1800”, Kassel, Universitätsverlag, 2007.

- Gama, R., “Tecnologia e Trabalho na História”, EDUSP, São Paulo, 1986, p. 74.

- Lühmann-Frester, H., “Europa in der frühen Neuzeit”, Böhlau Verlag, Vienna, 1999, p. 631.

- Gekeler, O., Johann Beckmann and the Consideration of Commodities and Technology in their Entirety, Sartoniana, 2, 139-171 (1989), p. 149.

- Beckmann, J., “Anleitung zur Technologie”, Vandenhoeck, Göttingen, 1777.

- Gekeler, O., Johann Beckmann and the Consideration of Commodities and Technology in their Entirety, Sartoniana, 2, 139-171 (1989).

- Frison, G., The First and Modern Notion of Technology from Linnaeus to Beckmann and Marx, Consecutio Rerum, Anno III, nº 6, 147-162, 2018.

- Beckmann, J., “Anleitung zur Technologie”, Vandenhoeck, Göttingen, 1777, pp 324-341.

- Gelman, Z., Angelo Sala, an Iatrochemist of the Renaissance, Ambix, 41, 142-160 (1994) (on p. 147/148).

- Gama, R., “ Engenho e Tecnologia”, Editora Duas Cidades, São Paulo, 1983, p. 342.

- Wisniak, J., Charles Edward Howard – explosives, meterorites and sugar, Educación Química, 23, 230-239 (2012). Kurzer, F., Life and Work of Charles Edward Howard, Annals of Science, 56, 113-141 (1999).

- Beckmann, J., “Anleitung zur Technologie”, Vandenhoeck, Göttingen, 1777, pp. 342-353.

- Bertholdus Niger (Berthold Schwarz), a legendary alchemist (14th century) from Freiburg, often credited with the invention of gun powder, is not a historical character. See R. Oesper, ‘Berthold Schwarz’, J. Chem. Educ., 16, 303-306 (1939).

- Reith, R., introduction to Meyer, T. (Ed.), “Luxus und Konsum – eine historische Annäherung”, Waxmann, Münster, 2003, pp. 18-19.

- Kraft, A., Chemiker in Berlin – Andreas Sigismund Marggraf (1709-1782), Jahrbuch des Vereins für die Geschichte Berlins, 2000, p. 23.

- Klemm,, F., “Geschichte der Technik”, Rowohlt, Hamburg, 1983.

- Saldaña, J., La historiografia de la tecnología en América Latina: contribución al estudio de su história intellectual, Quipu, 15, 7-26 (2013), p. 23.

- Krünitz, J., Oekonomische Encyclopaedie, Tressler, Brünn, 1790, Part 43, p. 4.

- Gekeler, O., Johann Beckmann and the Consideration of Commodities and Technology in their Entirety, Sartoniana, 2, 139-171 (1989), p. 154.

- Beckmann, J, “Entwurf einer Allgemeinen Technologie”, Göttingen, 1806.

- Gekeler, O., Johann Beckmann and the Consideration of Commodities and Technology in their Entirety, Sartoniana, 2, 139-171 (1989).

- Tomita, T., cited by O. Gekeler, op. cit., p. 146.

- Troitzsch, U. , postfacium, facsimile edition of Exner, Hoya, 1989.

- Gmelin, F, “Handbuch der Technischen Chemie”, Gebauer, Halle, 1795, p.1.

- Frison, G., Linnaeus, Beckmann, Marx and the Foundation of Technology between Natural and Social Sciences; a Hypothesis of an Ideal Type, History and Technology, 10, 161-173 (1993).

- Lühmann-Frester, H., Europa in der frühen Neuzeit, Böhlau Verlag, Vienna, 1999, pp. 632-634.

- Gillispie, C., The Discovery of the Leblanc Process, Isis, 48, 152-170 (1957).

- Graham-Smith, Science and Technology in Early French Chemistry, Colloquium ‘Science, Technologie et Industrie’, Oxford, 1979.

- Frison, G., “Technical and Technological Innovation in Marx”, History and Technology, 6, 299-324 (1998).

- Müller, A., Unbekannte Excerpte von Karl Marx über Johann Beckmann, in G. Bayerl, J. Beckmann, “Johann Beckmann (1739-1811)”, Waxmann, Münster, 1999.

- Frison, G., “Technical and Technological Innovation in Marx”, History and Technology, 6, 299-324 (1998).

- Beckmann, J., Anleitung zur Technologie, Vandenhoeck, Göttingen, 1777, in the preface.

- Crookes, W., speech at the BAAS meeting in Bristol, published in Science, edition from 28 October 1898, pp. 561-575. The Haber-Bosch process was invented only in 1908, but in 1898 there was already known the Frank-Caro process (1895).

- Latour, B., Woolgar, “Laboratory Life – the Construction of Scientific Facts”, Princeton University Press, 1971.

- Gekeler, O., Johann Beckmann and the Consideration of Commodities and Technology in their Entirety, Sartoniana, 2, 139-171 (1989), p. 148. In this sense, Beckmann would welcome Leo Hendrick Baekeland’s (1863-1944) invention of bakelite (1909).

- Sarton, G., “History of Science and the New Humanism”, Harvard University Press, 1962, pp. 161-162.