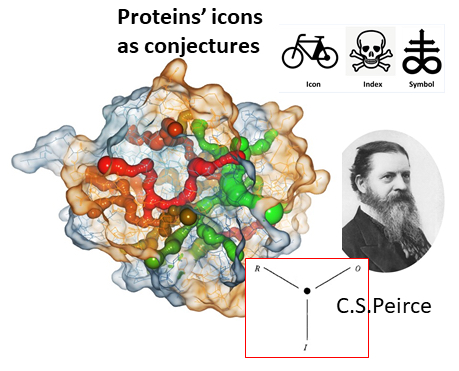

An Exercise of Applied Epistemology: Peirce’s Semiosis Implemented in the Representation of Protein Molecules

Published 2024-05-31

Keywords

- semiosis,

- protein models,

- iconographic communication,

- Peirce,

- Eco

How to Cite

Copyright (c) 2024 Elena Ghibaudi

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Abstract

In their disciplinary communication chemists make a broad use of iconographic means. In this paper, some aspects of the iconographic communication are discussed, with specific reference to the representation of protein molecules in the light of Peirce's and Eco’s semiotics. As far as Pierce’s thought is concerned, I discuss two triads (representamen, interpretant, and object) and (icon, index, symbol). Eco’s distinction between s-codes and codes is equally applied to the analysis of protein icons. The symbolic and iconic aspects of proteins’ representations are discussed, in the light of various conventions that regulate the use of shapes, lines, shadows, colors in the building up of images. The iconic aspect turns out to be the most surprising, not just because it makes 'visible' what is inherently invisible, but also because of its heuristic potential. I argue that the construction of protein images and their use in research qualify their epistemic status as that of conjectures.

References

- The present paper is dedicated to the memory of Luigi Cerruti, with whom the author shared long discussions concerning the issues addressed in this work; part of this work was presented by Cerruti and myself at the 21st conference of the International Society for the Philosophy of Chemistry (Paris 2017).

- J. Dalton, A New System of Chemical Philosophy, Bickerstaff, Manchester (UK), 1808, opposite p. 219. The plate can be seen at URL [https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/newsystemofchemi11dalt] Last accessed on March 5th 2024.

- A. H. Johnstone, Why is Science Difficult to Learn? Things Are Seldom What They Seem., J. Comp. Assist. Learn. 1991, 7, 75-83.

- M.P. Crosland, Historical Studies in the Language of Chemistry 1962, Harvard University Press, Cambridge (MS).

- W.P.D Wightman, Essay Review: The Language of Chemistry, Annals of Science 1963, 19, 259-267.

- B. Bensaude-Vincent (2002). Languages in chemistry. In M. J. Nye (Ed.), The Cambridge history of science (Vol. 5, The modern physical and mathematical sciences) (pp. 174-190).

- C. Jacob, Analysis and Synthesis: Interdependent Operations in Chemical Language and Practice, HYLE - Int. J. Phil. Chem. 2001, 7, 31-50.

- P. Laszlo, Chemistry, Knowledge Through Actions?, HYLE - Int. J. Phil. Chem. 2014, 20, 93-116.

- S. Weininger, Contemplating The Finger: Visuality and the Semiotics of Chemistry, HYLE - Int. J. Phil. Chem 1998, 4, 3-27.

- E. Francoeur, The Forgotten Tool: The Design and Use of Molecular Models, Social Studies of Science 1997, 27, 7-40.

- E. Francoeur, Cyrus Levinthal, the Kluge and the origins of interactive molecular graphics, Endeavour 2002, 26, 127-131.

- U. Klein , Paper Tools in Experimental Cultures, Stud. Hist. Phil. Sci. 2001, 32, 265-302.

- R. Mestrallet, Communication, Linguistique et Sémiologie. Contribution à l’étude de la sémiologie. Études sémiologique des systèmes de signes de la chimie, 1981, Bellaterra, Barcelona, p.21.

- R. Hoffmann, P. Laszlo, Representation in Chemistry, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 1991, 30, 1-16.

- R. Khanfour-Armalé, J.-F.Le Maréchal, Représentations moléculaires et systèmes sémiotiques, Aster, 2009, 48, pp. 63-88.

- M. Battersby, Critical Thinking as Applied Epistemology: Relocating Critical Thinking in the Philosophical Land-scape, Informal Logic 1989, 11, 91-100.

- M. Battersby, Applied Epistemology and Argumentation in Epidemiology, Informal Logic 2006, 26, 41-62.

- L. Laudan, Truth, Error, and Criminal Law, An Essay in Legal Epistemology, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2006, p. 2.

- C.S. Peirce, Writings of Charles S. Peirce: A Chronological Edition, Vol.8 (1890–1892), Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2010, p.21.

- Robert Marty, University of Perpignan, collected and analyzed 76 different definitions of sign found in Peirce’s texts, from 1865 to 1911: R. Marty, 76 Definitions of The Sign by C.S.Peirce, 2012, [http://perso.numericable.fr/robert.marty/semiotique/76defeng] Accessed March 5th 2024.

- CP 2.228 1897; the notation CP [volume#.paragraph#] refers to Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce, vol. 1-6 (Eds.: C. Hartshorne, P. Weiss); vol. 7-8 (Ed.: A. Burks), Harvard University Press, Cambridge (MS), 1931-35, 1958. Chronology added, following: Schriften von Charles Sanders Peirce, [https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schriften_von_Charles_Sanders_Peirce]. Accessed March 5th 2024.

- F. Merrell, Peirce, Signs, and Meaning, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 1997, p.13.

- CP 5.484 1907

- CP 2.148 1902

- CP 5.484 1907

- The essential Peirce, Selected philosophical writings, Vol. 2, (N. Houser, J.R. Eller, A.C. Lewis, A. De Tienne, C.L. Clark, D.B. Davis, eds), Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1998, p.274.

- G. Deledalle, Charles S. Peirce's Philosophy of Signs: Essays in Comparative Semiotics, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2000, p.18.

- Merrell 1997, op. cit., p. 26.

- Merrell 1997, op. cit., p. xii.

- CP 2.247 1903

- CP 2.276 1902

- CP 2.248 1903

- CP 2.249 1903

- MS 491 1903, quoted from D.R. Anderson, Creativity and the Philosophy of C.S. Peirce, Nijhoff, Dordrecht, 1987, p. 69.

- Discussion of these classifications is beyond the scope of this article. For further insight, see P. Farias, J. Queiroz, Notes for a dynamic diagram of Charles Peirce’s classifications of signs, Semiotica 2000, 131, 19-44; P. Farias, J. Queiroz, On diagrams for Peirce's 10, 28, and sixty-six classes of signs, Semiotica 2003, 147, 165–184; P. Borges, 79. Peirce’s System of 66 Classes of Signs. Charles Sanders Peirce in His Own Words: 100 Years of Semiotics, Communication and Cognition (T.Thellefsen and B. Sorensen, eds.), De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin-Boston, 2014, pp. 507-512.

- V. Romanini, Minute semeiotic: The Periodic Table of Classes of Signs, July 2014, DOI: 10.13140/2.1.4753.6327

- CP 2.302 1893

- J.C. Kendrew, G. Bodo, H.M. Dintzis, R.G. Parrish, H. Wyckoff, A three-dimensional model of the myglobin molecule obtained by X-ray analysis, Nature 1958, 181, 662-666.

- J.C. Kendrew, R.E. Dickerson, B.E. Strandberg, R.G. Hart, D.R. Davies, Structure of myoglobin. A three-dimensional Fourier synthesis at 2Å resolution, Nature 1960, 185, 422-427.

- CP 8.357 1908

- C.W. Morris, Foundations of the Theory of Signs, in International Encyclopedia of Unified Sciences, Vol. 1(2) (Ed.: O. Neurath), University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1938, p. 24.

- U. Eco, A Theory of Semiotics, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1976, p. 36.

- Eco 1976, op. cit., p. 37.

- Eco 1976, op. cit., p. 38.

- CP 5.171 1903

- CP 2.96 1902

- C.S. Peirce, Pragmatism as a Principle and Method of Right Thinking. The 1903 Harvard Lectures on Pragmatism, (Ed.: P.A. Turrisi), State University of New York Press, Albany (NY), 1997, p. 176.

- CP 5.438 1905

- R. Barthes, S/Z, Blackwell Publishing, New York, 1974, p. 120.

- CP 2.222 1903

- CP 2.279 1897

- Incidentally, these thoughts have clear implications regarding the current debate on Big Data and the ability of Artificial Intelligence to disclose meanings. AI spans huge amounts of data, but cannot disclose the symbolic content of an icon. Even further, AI is not capable of abductive reasoning.

- CP 2.430 1893

- CP 7.672 1903

- CP 5.181 1903

- CP 8.209, 1905

- Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Press release: The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2017, 2017 [https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/2017/press.html] Accessed March 5th 2024.