The Early Development of the Casale Process for the Production of Synthetic Ammonia (1917-1922). The protagonists, the technology, and a link between Italy and the United States

Published 2025-03-04

Keywords

- Terni,

- Italian Chemistry,

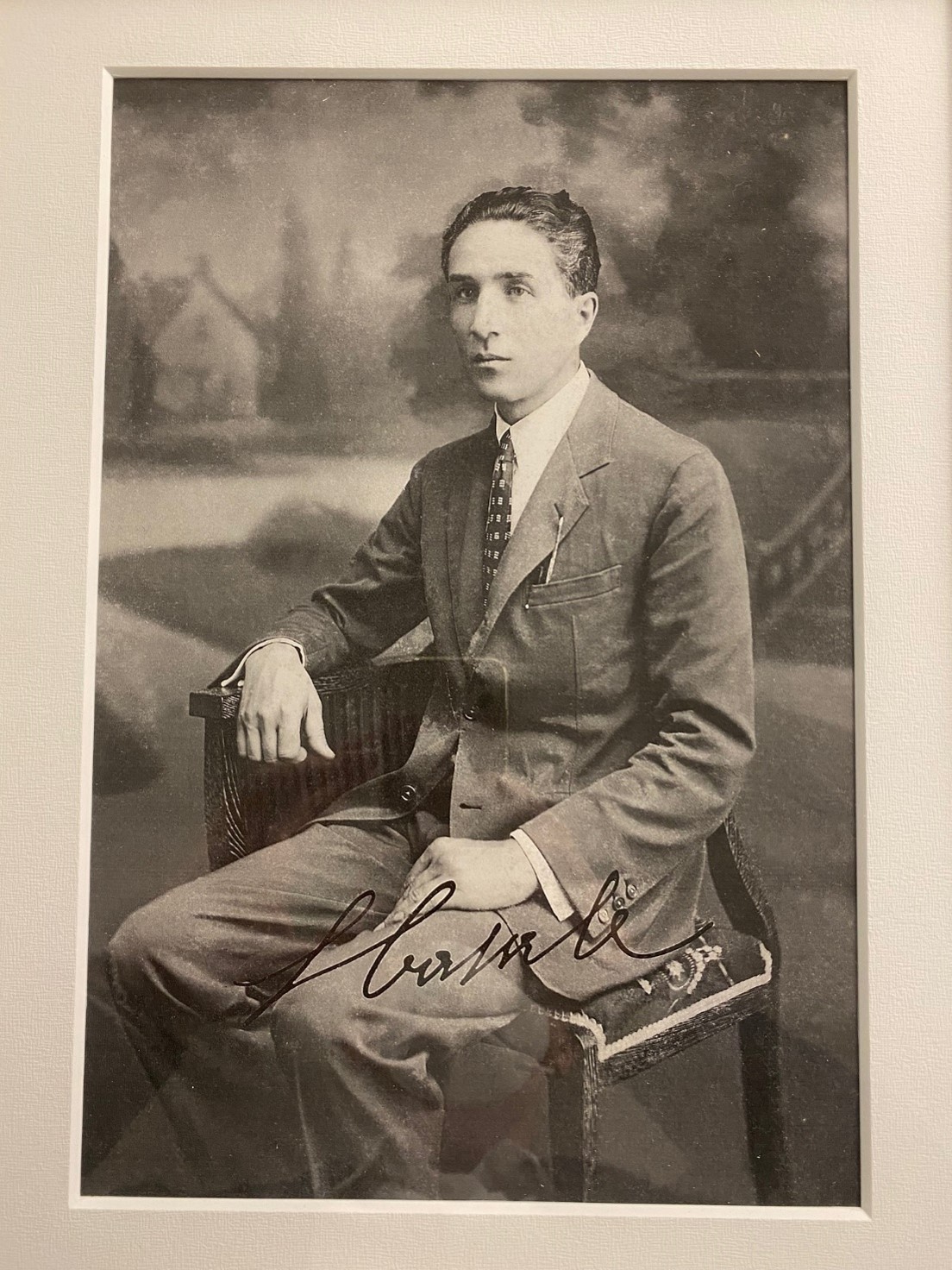

- Luigi Casale,

- Nitrogen Fixation,

- Casale Ammonia Process

- René Leprestre ...More

How to Cite

Copyright (c) 2024 Lorenzo Francisci, Anthony S. Travis

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Abstract

The Haber-Bosch process for the industrial synthesis of ammonia, originally intended for use in manufacture of nitrogen fertilizers, was inaugurated by BASF of Germany in 1913. During the First World War the process proved to be of tremendous value to Germany for the production of munitions. This was appreciated by the Allied nations, but, despite great efforts, they were unable to replicate the process prior to the cessation of hostilities. Notwithstanding tremendous postwar demand for nitrogen products to ensure national security in both munitions and fertilizers, BASF refused to license its ammonia process. This ultimately forced inventors and firms elsewhere to innovate based on their wartime research efforts. This paper provides an account of the emergence of the first successful rival to the BASF Haber-Bosch synthetic ammonia process, that of the Italian inventor Luigi Casale. To accomplish this goal, Casale in 1917 gained the support of the wartime chemical manufacturer Idros, at Terni, north of Rome, headed by the Franco-American entrepreneur René Leprestre. Better facilities for development of a working process, including byproduct hydrogen, were available at the works of the Rumianca company. Casale moved there in 1919. Leprestre brought in representatives of a group of investors from the United States to observe Casale’s process in action at the Rumianca works. However, disputes quickly emerged. Agreements were broken, followed by lengthy litigation, and the return of Casale to Idros at Terni. At Terni there were different problems. There, barriers to the supply of electricity were created, in part because the ammonia technology was perceived to be highly disruptive to another, well developed, local nitrogen process, that of calcium cyanamide. Compromises were reached. The outcome was the almost simultaneous foundation in 1921 of two companies, Ammonia Casale SA, in Lugano, Switzerland, which handled international licensing, and the Società Italiana per l’Ammoniaca Sintetica (SIAS) which absorbed the Idros works. In 1922 SIAS acquired a mothballed hydroelectric factory at Nera Montoro. It would serve as the industrial testing site for improvements in Casale’s process. The widespread, and rapid, dispersal of Luigi Casale’s highly successful synthetic ammonia process became an outstanding example of technology transfer from Italy during the early 1920s. This transfer included, through Leprestre, to the United States, as recently described in Substantia. The origins of the transatlantic interest can be discerned in the very earliest attempts by Casale to develop his novel ammonia technology, as described here.

References

- A. S. Travis, The Synthetic Nitrogen Industry in World War I. Its Emergence and Expansion, Springer, Cham, 2015, p. 9.

- V. Villavecchia, Dizionario di merceologia e di chimica applicata, vol. III, Hoepli, Milano, 1923, p. 58.

- O. Scarpa, L'industria elettrochimica dell'azoto atmosferico, Tipografia Editrice Italia, Roma, 1917, p. 8.

- L. F. Haber, The Chemical Industry (1900-1930). International Growth and Technological Change, Oxford University Press, London, 1971, pp. 100-101.

- W. Crookes, Science, New Series, 1898, 8, no. 20 (28 October), 561-575.

- See ref. 2, p. 62.

- E. Molinari, Trattato di chimica generale applicata all'industria, vol. I "Chimica Inorganica”, Hoepli, Milano, 1943, p. 825.

- See ref. 1, p. 42.

- On Haber, see, D. Stoltzenberg, Fritz Haber: Chemiker, Nobelpreisträger, Deutscher, Jude: Eine Biographie, VCH, Weinheim, 1994, and the English version, Fritz Haber: Chemist, Nobel Laureate, German, Jew, Chemical Heritage Press, Philadelphia, 2004; M. Szöllösi-Janze, Fritz Haber 1868-1934: Eine Biographie, VCH-Beck, Munich, 1998; B. Johnson, Making Ammonia: Fritz Haber, Walther Nernst, and the Nature of Scientific Discovery, Springer, Cham, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85532-1; D. Sheppard, Robert Le Rossignol: Engineer of the Haber Process, Springer, Cham, 2020, pp. 109-207.

- D. Maveri, La storia dell’azoto, Ipotesi, Milano, 1981, p. 82.

- In all, about 100,000 tons of nitrogen fertilizers were consumed in Italy (about 17,500 tons of nitrogen) in 1913, falling progressively to 88,000 tons in 1914, to 75,000 tons in 1915, 62,000 tons in 1916, 47,000 tons in 1917 and 1918. However, the need for nitrogen for the approximately 15 million hectares of Italian arable land would have require around 300,000 tons of nitrogen fertilizers (about 52,000 tons of nitrogen). See F. Zago, Le concimazioni chimiche in Italia, Firenze, 1923, pp. 21-25.

- A. S. Travis, Nitrogen Capture. The Growth of an International Industry (1900-1940), Springer, Cham, 2018, p. 229.

- A. Zambianchi, Giornale di Chimica Industriale e Applicata, 1923, 4, 171-176.

- With the Haber-Bosch process, coal consumption was one tenth of the arc process and one third of the calcium cyanamide process, while electricity consumption was fifty times lower and twelve times lower, respectively. See C. Rossi, Giornale di Chimica Industriale e Applicata, 1920, 6, 301-307.

- On Luigi Casale, see G. Marchese, Casale Luigi, Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Roma, 1978, https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/luigi-casale_res-263d981d-87ea-11dc-8e9d-0016357eee51_(Dizionario-Biografico)/ (accessed on 05 June 2024).

- D. K. Barkan, Walther Nernst and the Transition to Modern Physical Science, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999; P. Coffey, Cathedrals of Science: The Personalities and Rivalries that made Modern Chemistry, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2008.

- Acciai Speciali Terni Historical Archive, II deposit, folder 86, dossier 11, copy of the deed of incorporation of Idros di Terni by deed of the notary Umberto Rimini, 19 February 1916.

- Ibid, List of members of the Board of Directors of Idros in 1916.

- Central State Archives, Ministry of Arms and Ammunition Fund, Original Contracts, folder 9, dossier 778, copy of the contract between Idros and the Military Administration for the supply of 36,000 bombs, 29 November 1916.

- Ibid, copy of the contract between Idros and the Military Administration for the supply of 237.75 cubic metres of oxygen, 29 Novembre 1916.

- Acciai Speciali Terni Historical Archive, II deposit, folder 103, dossier 7, minutes of the meeting of the Executive Committee of Carburo, 22 September 1915. See also “Andreucci Carlo’s Patent 483-227”, cited in Annals of Applied Chemistry, 1917, 7-8, 98.

- As for the catalyst, it was a compound of inorganic and organic matter (salts, oxides, metals, alkali metals, earth alkaline metals, earth metals, carbon and metalloid oxides). See Accademia Nazionale delle Scienze detta dei XL Historical Archive, Nicola Parravano Fund, folder 22, dossier 221, copy of the patent “Metodo industriale ed apparecchio per la produzione sintetica dell’ammoniaca, mediante un nuovo catalitico di grande rendimento” of Luigi Casale, Carlo Andreucci, Mario Santangelo, 18 luglio 1917.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, copy of the patent “Metodo ed apparecchio per produrre da idrogeno miscele di azoto, idrogeno od azoto” of Luigi Casale, 12 July 1920.

- A. M. Falchero, Italia contemporanea, 1982, 146-147, 67-92.

- See ref. 22, copy of the agreement between Casale and Lepreste, 2 August 1919.

- Ibid, copy of the judgement of the Turin Court of Appeal in the Rumianca-Casale case, April 1929, p. 2.

- State Archive of Terni, Siri Fund, folder 3699, letter from Luigi Casale to Alfonso Vitale, 25 August 1919.

- Ibid, Letter from Luigi Casale to Alfonso Vitale, 13 September 1919.

- See ref. 22, copy of the patent “Apparecchio di catalisi per la sintesi dell’ammoniaca” of Luigi Casale, René Lepreste, 21 September 1920.

- Ibid. See also copy of the patent “Perfezionamento nell’apparecchio catalitico per la sintesi dell’ammoniaca” of Luigi Casale, René Lepreste, 15 February 1921.

- B. Waeser, The Atmospheric Nitrogen Industry: With Special Consideration of the Production of Ammonia and Nitric Acid (transl. Ernest Fyleman), vol. I, P. Blakiston's Son & Co., Philadelphia, 1926, p. XVII. Fyleman was a chemist associated with the London-based J.F. Crowley and Partners engineering consultancy of B. Waeser, Die Luftstickstoff-Industrie, mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der gewinnung von ammoniak und salpetersaure, Otto Spamer, Leipzig, 1922, with an introduction by J. F. Crowley. Crowley and Partners represented Ammonia Casale in the UK.

- Acciai Speciali Terni Historical Archive, Archives Acquired Fund, Carburo, register 64, minutes of the meeting of the Board of Directors of Carburo, 2 May 1921.

- Ibid, minutes of the meeting of the Board of Directors of Carburo, 27 April 1921.

- Ibid.

- Acciai Speciali Terni Historical Archive, Archives Acquired Fund, SIAS, register 1, minutes of the meeting of the Board of Directors of SIAS, 6 February 1922.

- Ibid, minutes of the meeting of the Board of Directors of SIAS, 8 October 1921.

- B. Molony, Technology and Investment: The Prewar Japanese Chemical Industry, Mass: Council on East Asian Studies/Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1990. See also https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/l-industria-dei-composti-azotati_(Il-Contributo-italiano-alla-storia-del-Pensiero:-Tecnica)/ (accessed on 10/05/2024).

- See ref. 36, minutes of the meeting of the Board of Directors of SIAS, 27 June 1922.

- See ref. 22, copy of the judgement of the Turin Court of Appeal in the Rumianca-Casale case, April 1929, p. 2.

- Ibid, pp. 8-12.

- Ibid, pp. 14-16.

- Ibid, pp. 16-18.

- Ibid, pp. 59-64.

- Ibid, pp. 104-106.

- Ibid, pp. 101-103.

- https:///inflationhistory.com/it-IT/?currency=ITL&amount=2500000&year=1929 (accessed 25 May 2024).